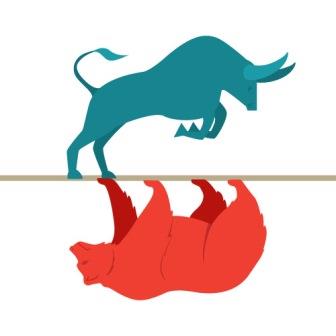

The current crisis allows us to rethink on inflation targeting as monetary strategy.

Four years have passed since RBI adopted inflation targeting

as its monetary policy strategy. The Monetary Policy Framework Agreement (MPFA)

was signed between the Government of India and RBI on February 20, 2015.

Subsequently, flexible inflation targeting (FIT) was formally adopted with the

amendment of the RBI Act in May 2016. Under the inflation targeting regime, the

primary objective of monetary policy is to maintain price stability while

keeping in mind the objective of growth.

Before the adoption of the inflation targeting

regime, the central bank was following a multi-indicators approach. The

approach was followed for 17 years from 1998 to 2018. However, post Global

Financial Crisis of 2008, the multi-indicators approach of RBI came under

criticism due to the co-existence of high inflation rate and lower growth rate.

Consequently, the expert committee formed for revisiting the monetary policy

framework of RBI recommended the adoption of an inflation targeting regime. The

committee proposed flexible inflation targeting with consumer price index (CPI)

as the nominal anchor. The target was fixed at 4 per cent with a band of +/- 2

per cent.

If we analyse the inflation rate from May 2016

onwards, one could say that barring a few months, the inflation targeting

regime helped ensure price stability. However, lately, the inflation targeting

regime has come under criticism. For instance, in the initial months of FY19, a

low inflation rate co-existed with a declining growth rate. Similarly, the

inflation rate in December 2019 crossed the upper band of 6 per cent, even when

the economy was experiencing an slowdown.

The inflation rate remained above the upper

range for three months, before falling back to 5.91 per cent in March 2020. In

the wake of rising inflation, RBI’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) in the

bi-monthly meetings that took place in December and February decided to keep

rates unchanged. RBI maintained status quo even when there was chorus for a

rate cut.

The high inflation rate was largely due to

increasing vegetable prices, mainly the ‘onion shock’. For instance, in

December 2019, overall inflation rate was at 7.35 per cent, with food inflation

rate at 14.19 per cent. Vegetable prices registered a growth of 50 per cent December

2019. However, in the same month, core inflation i.e. inflation less food and

fuel, was much lower at 3.7 per cent. The low core inflation rate reflects the

tepid demand in the economy.

Thus, even when the economy was experiencing a demand slowdown, the central bank’s decision was guided by rising food inflation rate. The monetary policy tool has only limited impact, or one could say, no impact in controlling the food inflation rate. In India, rising food prices are mainly a supply-side issue, where the central bank has only a limited role to play. Food and beverages have a share of around 45 per cent in CPI, the nominal anchor used by RBI. Hence, the direction of overall inflation rate in the economy is influenced by where the food prices are heading towards.

Currently, the economy is passing through an unprecedented phase with economic activities being badly hit by Covid-19 and national lockdown. Low crude oil prices could act in favour of bringing down the inflation rate. However, amid the lockdown and supply disruption, there are chances that food prices could spiral up. Consequently, RBI has to deal with a slowing economy and rising inflation rate. And, the central bank would be in a difficult spot, as it is following the inflation targeting regime. The current crisis provides us the opportunity to rethink whether the inflation targeting regime is the best monetary policy strategy for India.

First published in Economic Times.