It’s been four years since RBI adopted inflation targeting as its monetary policy strategy. The Monetary Policy Framework Agreement (MPFA) was signed between the Government of India and RBI on February 20, 2015. Subsequently, flexible inflation targeting (FIT) was formally adopted with the amendment of the RBI Act in May 2016. Under the inflation targeting regime, the primary objective of monetary policy is to maintain price stability while keeping in mind the objective of growth. In August, 2016 Government notified an inflation target of 4 percent within a band of +/- 2 percent. The headline Consumer Price Index (CPI) was selected as the nominal anchor under the inflation targeting framework. The framework is applicable for 5 years, starting from August 5, 2016 to March 31, 2021. As per the notification, if the average inflation rate is above the upper tolerance level of 6 percent or less than the lower tolerance level of 2 percent for any three consecutive quarters, it would mean the failure to achieve inflation target.

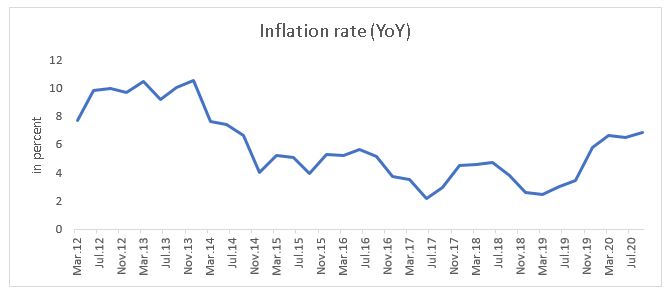

The figure below shows the inflation rate in India, pre and post the adoption of inflation targeting framework.

It is evident that except in the last quarter of FY20 and the first two quarters of FY21, inflation rate has been in the permissible range. In December’19, inflation rate breached the upper band of 6 percent, and reached 7.35 percent. The rise in inflation rate was mainly contributed by the spike in food prices. For instance, food inflation rate cloaked a double- digit rate of 12.16 percent in December’19. It was mainly due to increasing vegetable prices, mainly the ‘onion shock’. Vegetable prices registered a growth rate of 50 percent in the same month. And, the food inflation rate cooled down to 7.8 percent in March’20. However, with the national lockdown imposed due to Covid-19, economy faced severe supply side issues. As a result, food inflation climbed to 10.47 percent in April’ 20, with the general inflation rate at 7.2 percent. As food and beverages account for nearly 45 percent CPI, movement in food prices determines the overall trend in the general inflation rate. In the graph given above, it could be seen that inflation rate was at its lowest level in the first quarter of FY18 at 2.2 percent. And, in the same quarter, food inflation rate registered a negative growth rate of 2 percent.

The question that is being debated is how far the Central Bank policies will exert influence in controlling the food inflation rate in India. In India, rising food inflation rate has generally been a supply side issue. And, it could be seen that the rising food inflation rate always acted as an impediment for the RBI in formulating its monetary policy measures. To quote RBI Governor, from his statement dated December 4, 2020 “A small window is available for proactive supply management strategies to break the inflation spiral being fuelled by supply chain disruptions, excessive margins and indirect taxes. Further efforts are necessary to mitigate supply-side driven inflation pressures”. The role of the Central Bank in dealing with supply side issues in the economy is also limited.

In the initial years of inflation targeting regime, low food prices and declining crude oil prices benefited the Indian economy in controlling inflation rate. However, in the succeeding years as food prices started rising, general inflation rate also rose above the permissible level. RBI was having tough ride as it had to deal with rising inflation rate on the one hand, and a slowing economy on the other hand. Indian economy registered one of the lowest growth rates of 4.2 percent in FY20, and in the last quarter of FY20, GDP growth rate stood at 3.09 percent. During the same period, inflation rate as measured by CPI stood at 4.7 percent and 6.7 percent, respectively. And, MPC’s decision on interest rate were mainly guided by the trend in inflation rate, though other factors were also considered.

Inflation targeting regime would work better in developed countries, where inflation is mainly contributed by demand side factors. However, in a developing country like India, it is mainly the supply side factors that influences inflation rate. More than the Central bank, government can better handle the supply side issues in the economy. Similarly, in this era of ‘hot money’, inflation targeting regime won’t work best for India.

Presently, discussions are going on the need to ease inflation target range. However, easing the inflation target range won’t serve the purpose as the nominal anchor used in the inflation targeting framework has a higher share of volatile items like food and fuel. As the current regime of inflation targeting ends on March 31, 2021, there is a need to deliberate on whether inflation targeting is the best monetary policy strategy for India.

The figure below shows the inflation rate in India, pre and post the adoption of inflation targeting framework.

It is evident that except in the last quarter of FY20 and the first two quarters of FY21, inflation rate has been in the permissible range. In December’19, inflation rate breached the upper band of 6 percent, and reached 7.35 percent. The rise in inflation rate was mainly contributed by the spike in food prices. For instance, food inflation rate cloaked a double- digit rate of 12.16 percent in December’19. It was mainly due to increasing vegetable prices, mainly the ‘onion shock’. Vegetable prices registered a growth rate of 50 percent in the same month. And, the food inflation rate cooled down to 7.8 percent in March’20. However, with the national lockdown imposed due to Covid-19, economy faced severe supply side issues. As a result, food inflation climbed to 10.47 percent in April’ 20, with the general inflation rate at 7.2 percent. As food and beverages account for nearly 45 percent n CPI, movement in food prices determines the overall trend in the general inflation rate. In the graph given above, it could be seen that inflation rate was at its lowest level in the first quarter of FY18 at 2.2 percent. And, in the same quarter, food inflation rate registered a negative growth rate of 2 percent.

The question that is being debated is how far the Central Bank policies will exert influence in controlling the food inflation rate in India. In India, rising food inflation rate has generally been a supply side issue. And, it could be seen that the rising food inflation rate always acted as an impediment for the RBI in formulating its monetary policy measures. To quote RBI Governor, from his statement dated December 4, 2020 “A small window is available for proactive supply management strategies to break the inflation spiral being fuelled by supply chain disruptions, excessive margins and indirect taxes. Further efforts are necessary to mitigate supply-side driven inflation pressures”. The role of the Central Bank in dealing with supply side issues in the economy is also limited.

In the initial years of inflation targeting regime, low food prices and declining crude oil prices benefited the Indian economy in controlling inflation rate. However, in the succeeding years as food prices started rising, general inflation rate also rose above the permissible level. RBI was having tough ride as it had to deal with rising inflation rate on the one hand, and a slowing economy on the other hand. Indian economy registered one of the lowest growth rates of 4.2 percent in FY20, and in the last quarter of FY20, GDP growth rate stood at 3.09 percent. During the same period, inflation rate as measured by CPI stood at 4.7 percent and 6.7 percent, respectively. And, MPC’s decision on interest rate were mainly guided by the trend in inflation rate, though other factors were also considered.

Inflation targeting regime would work better in developed countries, where inflation is mainly contributed by demand side factors. However, in a developing country like India, it is mainly the supply side factors that influences inflation rate. More than the Central bank, government can better handle the supply side issues in the economy. Similarly, in this era of ‘hot money’, inflation targeting regime won’t work best for India.

Presently, discussions are going on the need to ease inflation target range. However, easing the inflation target range won’t serve the purpose as the nominal anchor used in the inflation targeting framework has a higher share of volatile items like food and fuel. As the current regime of inflation targeting ends on March 31, 2021, there is a need to deliberate on whether inflation targeting is the best monetary policy strategy for India.